Jackson County WV: Rural Animal Shelter Challenges and Successes

In October, we visited Jackson County Animal Shelter in Cottageville, West Virginia. Teresa has been the Humane Officer running the shelter there for the last 8 years. Prior to that she volunteered and then became a part-time employee.

In 2013, when Teresa began at the shelter, its live-release rate was only 25%. Euthanizing animals was part of her job, but it broke her heart. When the Humane Officer position opened, she jumped at the chance to change the narrative. Since then, the shelter only euthanizes for extreme behavior or medical reasons.

Like most shelters these days, JCAS is full. The day we visited, they had 83 dogs housed between their two original shelter buildings and the new shelter, which opened two years ago on the same campus.

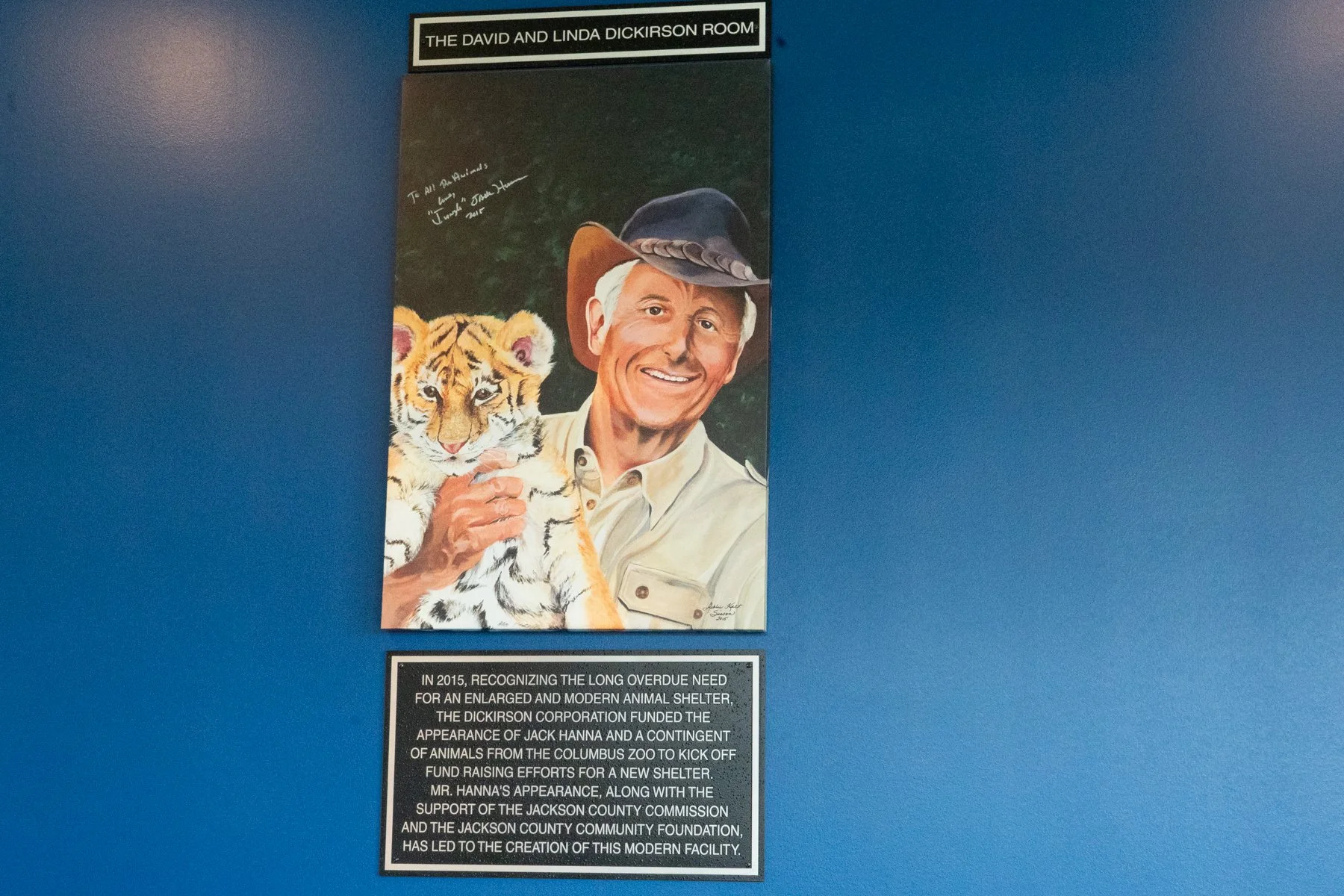

JCAS is a municipal shelter, but funding for the new shelter building was kicked off following a visit from Jack Hanna (yes, that Jack Hanna), who donated the first 10K. The remaining 1.8 million in funding for the building came from generous local donors and municipal funds.

The building is beautiful with clean lines, bright, airy spaces, and dedicated rooms for grooming, intake, cats, plus two separate dog wings (one for quarantine/intake and one for adoption). The nearly completed surgery room was awaiting final inspection. Once operational, a contracted veterinarian will spay/neuter shelter animals one day a week. JCAS has six part-time employees; Teresa is the only full-time employee.

One of the old shelter buildings was housing 23 small dogs seized from a hoarding situation. They were mixed-breed, possibly a Chihuahua or rat terrier. Two of the dogs were pregnant, and another gave birth at the shelter to a single surviving puppy (plump and healthy). A third pregnant dog and two others had yet to be trapped at the property where they were seized.

While we were visiting, the staff heard about a potential additional hoarding case. Hoarding situations seem to be popping up everywhere these days like pimples on a teenager. Dealing with them can stretch a shelter too thin. I asked Theresa where she would put the dogs if they came to the shelter, and she said they would set up the garage area with crates, and then try to work with rescues.

Every shelter needs to have a plan for potential hoarding situations. While there are rescue groups throughout the US that can help, the immediate need often falls to the local shelter. Shelter staff, animal advisory committees, and municipal officials should have a plan in place, much like they would for a weather disaster. The economy likely contributes to the current increase in hoarding situations (expected to involve a quarter million animals this year in the US alone), and mental health issues clearly do as well, but too often it is simply a well-intentioned person who gets in over their head trying to help. By the time hoarding situations come to light, the numbers and the damage are horrific, but they didn’t get that way overnight. We need ways to find these situations before they spiral out of control. That won’t be easy, but it means paying attention in new ways.

Committing not to euthanize for space means the shelter often houses dogs for months or even years. The F puppies (all with names starting with the letter F) came to the shelter when they were four months old. Now two years old, they have grown up at the shelter. Whether they are still adoptable, whether that will happen, and whether a quality-of-life decision should be made are just a few more of the heartbreaking elements of sheltering.

Remaining full also means the shelter does not take many owner-surrendered dogs. They offer resources like food and spay/neuter services, and place the would-be surrenderer on a waiting list.

It’s a challenging situation that is all too familiar in too many places. I asked Teresa what happens to the dogs they turn away, and she said she doesn’t know. She does take a picture of the dogs just in case they turn up as a ‘stray’ later, and will prosecute them.

Turning away dogs at municipal shelters seems inconsistent with the mission of animal services, yet many shelters still do so. There is pressure from national animal-welfare organizations, the public, and, often, shelters themselves to achieve ‘no-kill’ status. While there is no official number, most people and organizations interpret this to mean that 90% of animals that enter the shelter get out alive. The number is arbitrary, and I believe it is the primary driver of our current stray crisis.

No one wants to kill dogs, least of all animal shelter employees who literally dedicate their lives to saving them, but when you have a finite number of kennels and resources, you quite simply cannot save them all. Beyond that, I would argue that keeping an animal alive is not the same as saving their life. Having walked through nearly 200 shelters observing thousands of dogs in kennels by now, the stress of that life is not something I would wish on any dog – no matter how resilient. It is time for better solutions.

The shelter’s evolution and much of its progress have come in no small part because of the help of ARF (Animal Rights Furever), a non-profit with a mission to help the shelter. They purchased the transport van, buy supplies the shelter needs but does not have in its budget, cover some medical needs, and help community members with animal-related needs.

Teresa believes what is needed to bring real change in Jackson County is Education. Often, it is simply that people don’t know what humane care for dogs looks like – that they need annual vaccinations, preventatives, deworming, etc. Much of her job is providing that kind of education. Teresa and the staff work to educate the next generation by visiting the local schools and hosting children and teen groups at the shelter.

[In February, Who Will Let the Dogs Out will be launching a new grant program to provide materials to teach responsible pet ownership in schools. We’ll be sharing the details soon!]

I asked Teresa why she stays in a job that must be frustrating at times and too often heartbreaking. Before she could answer, Suzette, a supporter and journalist who was there to cover our visit, said, “She’s crazy, stubborn, and big-hearted.” Teresa smiled and replied, “I am crazy.”

It’s a good kind of crazy, and Jackson County is lucky to have her. If you’d like to support the work Teresa, her staff, and ARF are doing to improve the lives of animals (and people) in Jackson County, consider shopping their Amazon wishlist:

https://www.amazon.com/hz/wishlist/ls/1A0J6HFC02FP8

Currently, more animals leave the shelter through rescue than adoptions. If you are a rescue who can help, reach out to Dreama or Teresa at the shelter (jcas@jacksoncountywv.com).